Towards the end of the novel, the narrator says of L, whom she both admires and loathes, and by whom she knows herself to be loathed in turn: 'He drew me with the cruelty of his rightness closer to the truth.' We might say the same of Cusk, our arch chronicler of the nullifying choice between suffocation and explosion.

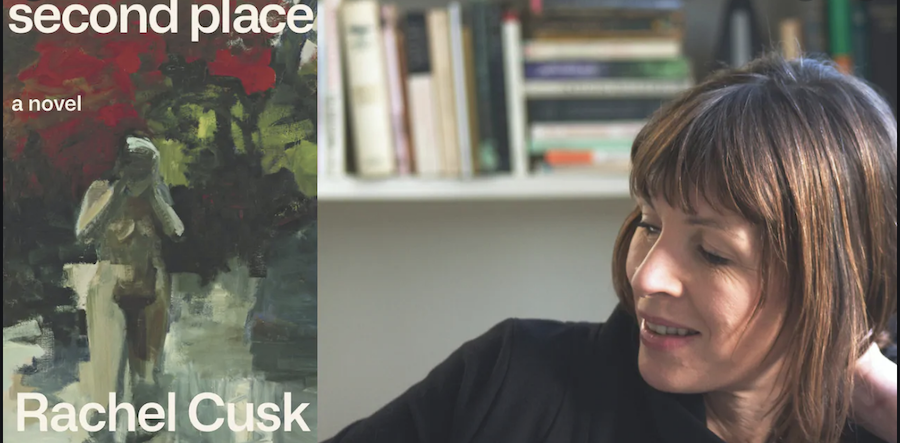

The novel’s emotional nuance, its stylistic poise, has been as perfectly and painstakingly constructed as the life it describes, only to be blown apart by a flat and shattering statement, weighted around a central, immovable truth. Second Place, it turns out, is a novel less about property, and more about the boundaries and misplaced emotional investment for which property is a proxy. This is, however, a Cusk novel, and in Cusk novels the surface, as experienced by reader and characters alike, invariably proves too fragile to be trusted. On the surface, then, this is a novel of glaring privilege, steeped in a mode of middle-class existence so rarified that the 'lower things' must never be allowed to intrude.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)